Polite Little Girl - No More

“I cannot forgive the men who abused me. I do not know how to and they do not deserve it. I forgive myself instead," writes Samira Gupta, in this empowering personal essay.

Listen to this immaculate essay in the calm, brave voice of

:

I was taught to say sorry and thank you from a very young age. Polite little girls pleased people.

I apologized for mistakes I did not make, was punished for opinions I was not meant to have; for speaking loudly and laughing freely. Polite little girls only smiled shyly.

I spoke softly, responded only when asked a question and sat quietly while adults spoke. I accepted body shaming as humour and brushed it off with a smile. Polite little girls learnt from their elders.

Hot tears ran down my cheeks

When I was eleven, a tailor came home to get my measurements for a kurta set. It was evening, just before dinner. I had bathed and was wearing a red and blue gingham nightie with smocking in the front.

My breasts were just beginning to grow. I had not worn a bra, thinking I would be going to bed soon.

The tailor took my measurements in front of my mother. Once he was done, I went to complete my homework. My study room was a small makeshift space nestled between the main door and the lift. My parents were in the drawing room, watching TV. My little brother was playing in his room.

The tailor was about to leave. Then he stopped and asked me if he could recheck his measurements once. He might have made a mistake. I said okay. I was sitting on the chair facing the desk, with my book open in front of me. He came from behind and cupped my breasts in both his hands and squeezed. It hurt me. I did not say anything.

He squeezed again. I did not say anything. Then he gently slipped his hand inside my nightie and felt my tiny, underdeveloped breasts. He squeezed again. Harder this time. I felt shooting pain and cried out. I must have been loud because he left in a hurry, mumbling something to himself.

I remained seated, stunned. Hot tears ran down my cheeks. My breasts ached. I felt like I needed to bathe again. I went to my parents and told them what the tailor had done.

The rest of the memory is vague. I lay down on the sofa with red puffy eyes. My brother came to ask what had happened to me. My mother said it was nothing. I remember hushed conversations between my parents. I went to school the next day, feeling different. My friends were the same, oblivious to what had happened to me. I did not tell them anything. I did not tell anyone.

A week later, the tailor arrived with my stitched kurta set. My father opened the door. He took the parcel and reprimanded him gently. I was standing with my back to the wall, next to the door. The tailor apologised profusely. My father shut the door.

I remained standing, frozen, staring at the floor. For a fleeting moment I thought I had imagined it all. Then a deep sense of dread set it. Were we supposed to be quiet when something like this happened? My eleven-year-old self could not make sense of it. I wanted to slap the tailor. I wanted to scream and cry. I wanted to take him to the police. But I was too young to have an opinion. I remained quiet, like a polite little girl.

The tailor had been forgiven. Life continued. I swallowed my anger and moved on, like a polite little girl.

This is no way to speak to a beggar

A few years later, outside a crowded cinema hall, a homeless person came towards me and tried to touch my breasts. I screamed at him with all my might. “How dare you!” I yelled. My mother was stunned. She looked at me angrily. “Keep your voice down. This is no way to speak to a beggar,” she reprimanded. I looked at her aghast. “He tried to touch my breasts, Mamma,” I said. “Oh!” she said and walked on.

The abuser had been forgiven. We watched the movie and came home. Life continued. I swallowed my anger and moved on, like a polite little girl.

I did not want to be the cause of the discord

Eight years later, my boyfriend fell sick. He was alone at home. I decided to skip college and spend the day with him. He was thankful for my company but too weak to stay awake. I encouraged him to take a nap. I had a good book with me. Just as I was settling in to read, his father came home for lunch. He was surprised to find me there. I told him I would stay till evening and he could go back to work. He decided not to.

I sat with my boyfriend’s father till he finished eating and then returned to my book. He was about to go take a nap, when he paused outside his room and asked, “I’m a good palm reader. Would you like me to read your hand?” I was not sure. “Try it. It will be fun,” he urged. I did not want to offend him.

He invited me to his room. “You have been deeply hurt as a child. You need to let go of the shame.” “Okay…” I said hesitantly, uncomfortable with the topic. “Why don’t we try something. Press my legs as an act of seva (service). You will feel better.” “I’m okay, Uncle.” I said. “Give it a try,” he urged. I felt trapped and did as I was told. Eventually he began panting heavily and through his thick track pants I noticed a firm, hard bulge. I told him I had to leave. I picked up my bag and walked out. I forgot to take my book.

When my boyfriend woke up and realised I had left, he called me. I told him what had happened. “Should I speak to my father?” he asked. “No. Let it be.” I did not want to be the cause of discord in his family.

My boyfriend forgave his father. The relationship ended. I swallowed my hurt and moved on, like a polite little girl.

She would not be a polite little girl

When I was thirty-four years old, my daughter was born. I held her in my arms and felt my world change forever. I was no longer a polite little girl. In that moment between sleep deprivation and extreme euphoria, I made a promise – to myself and to my daughter. She would not be a polite little girl.

I realised that polite little girls, who turn into polite little women breed the next generation of polite little girls. I am determined to break the cycle.

Forgiveness is the greatest and quietest act of courage. I cannot forgive the men who abused me. I do not know how to and they do not deserve it.

Instead, I forgive myself.

I kiss the little girl on her forehead and let go of shame. I hug the angry teenager outside the cinema hall and let go of anger. I sit next to the young woman, and hold her hand. I let go of hurt. One by one they smile.

“Thank you,” they say. I close my eyes and see my daughter – running wild and free in a meadow. I am running with her, laughing.

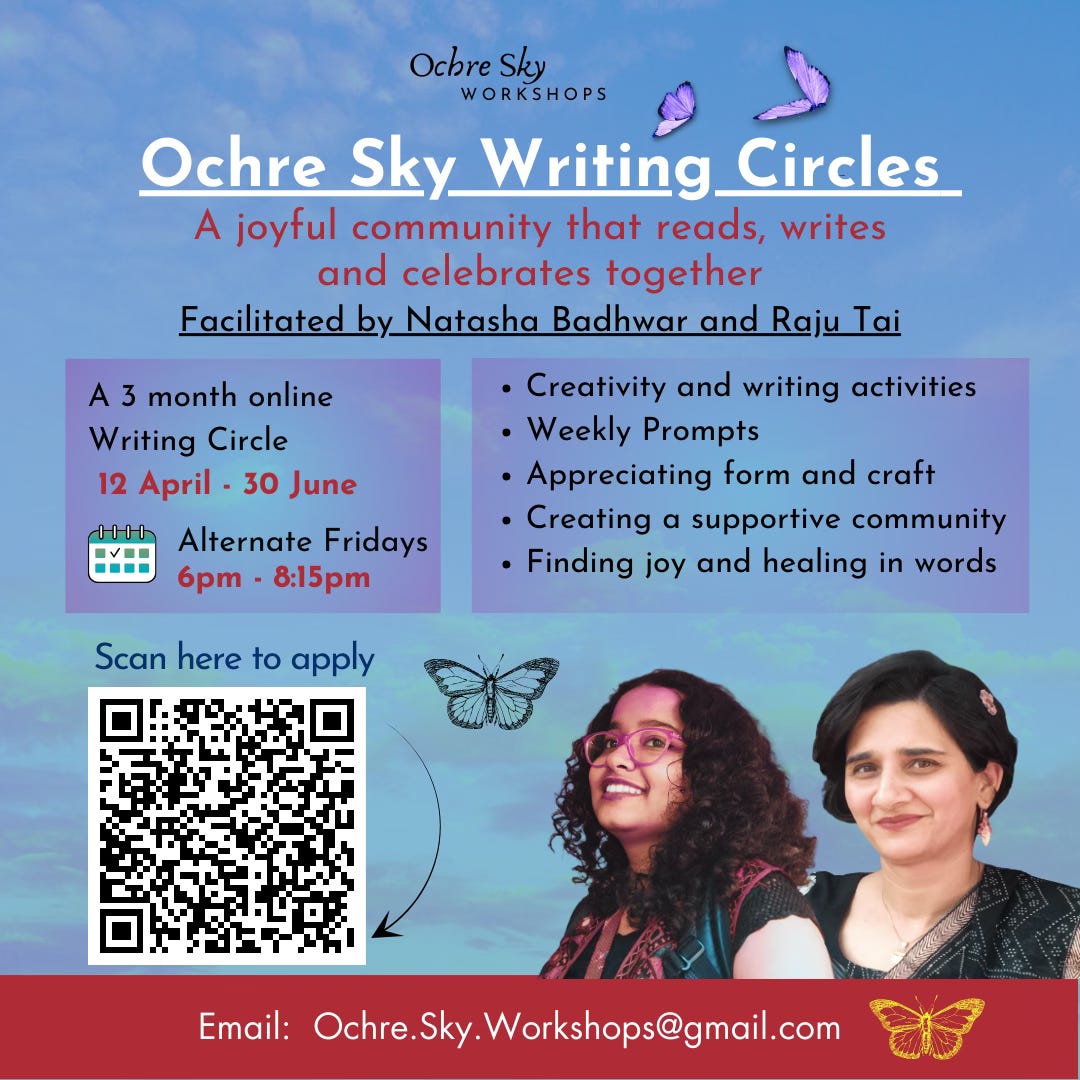

is an artist and writer, who has been a passionate participant on the Ochre Sky Writing workshop and Ochre Sky Writing Circle.

She wrote this essay in the Ochre Sky Memoir Workshop in response to the prompt, Forgiveness.

I am crying as I read this in a cab. My heart is racing in rage for all those polite little girls who were let down - not just by their abusers - but by people they loved and trusted. I honestly think that mothers who choose to heal themselves and break the cycle of silence are the closest we have to Gods. You are a God, Samira ❤️

Thank you for bringing this story to us and reminding us why we do what we do as mothers and writers, Natasha ❤️

Thank you for reading my story, for your comments, for sharing your own stories and for your courage. I am deeply moved, humbled and grateful to have this community. I hope that our collective voices help to heal our wounds and empower our children ⭐