The Innate Dignity Of Children

There is palpable hurt in her words. Her understanding of the world is making her uncomfortable in it. I listen and say a few words, but mostly I let her feel her feelings.

“America is much better than India,” the new child in the park announces to the group my children are in, unsure of whether she wants to be accepted by them or whether it will be easier to reject them first.

“English is better than Hindi,” she adds. “American potato chips are better.”

The older children engage in a discussion with the new child in our neighborhood. They begin to speak to her in English. Our youngest child comes home to me and asks me about hierarchies in the world.

“Is America a bad place, Mamma,” she asks. “Why was that girl trying to make it sound better than here? Is India the best, Mamma. Is it the only good place?”

“No, Baba,” I say. “America is just as nice.”

“What about the yellow team in Chak De India,” she asks me a few days later. “Are they bad people?” She is trying to understand the other. Can we be different without needing to believe that the other deserves our hatred?

“The young women in Chak De India are playing hockey for their country. Too many people are involved in the game when it is being played between teams of two countries. They are not enemies, they are the Australian hockey team. Remember, they become friends with the Indian team later,” I say to her.

“Just like in my school,” she says. “Everytime the teacher leaves us alone in the classroom, it becomes a boys vs. girls free for all. We start taunting each other. I don’t like it.”

There is palpable hurt in her words. Her understanding of the world as she grows up is making her uncomfortable in it. I listen and say a few words, but mostly I let her feel her feelings. Make connections on her own.

In Grade 2, she comes back home one day after a class trip to the zoo. She doesn't want to go to school the next day. She looks exhausted in the morning, but as soon as we agree to let her rest at home, she recovered her full energy.

“You are a Muslim,” her friend had said to her in the zoo. She narrates the incident to me.

“I’m a Muslim, so what, I said,” she gestures with her hands and shrugs. “There were three men walking in the zoo wearing kurta-pajamas and a cap on their heads. Ananya pointed towards the men and said, that is your father. Why did she say that to me? She knows my father. She has seen him school.”

My child puts her hand at the back of her head and shows me. I imagine she means a skullcap.

I am speechless. I wonder what kind of conversations Ananya overhears at home. What does she watch on TV? What makes her want to remind her friend that she is different. That she can be mocked for being a Muslim.

“Later when I took out my handkerchief to wipe my hands, Ananya said it was a Muslim handkerchief.” I had given my child a large white handkerchief in the morning when I couldn’t find any other from her own set. It does belong to her father.

My daughter and I laugh together at the idea of a Muslim handkerchief. Neither of us will be comfortable using it in public for a while.

“Earlier Ananya was my best friend, but then she began to lay down rules. You cannot talk to anyone else if you want to remain my best friend. You cannot sit with anyone else.”

These children are barely 7 years old yet. Ananya greets me with a cheerful smile every time she sees me when school is over. I nod and smile specially for her.

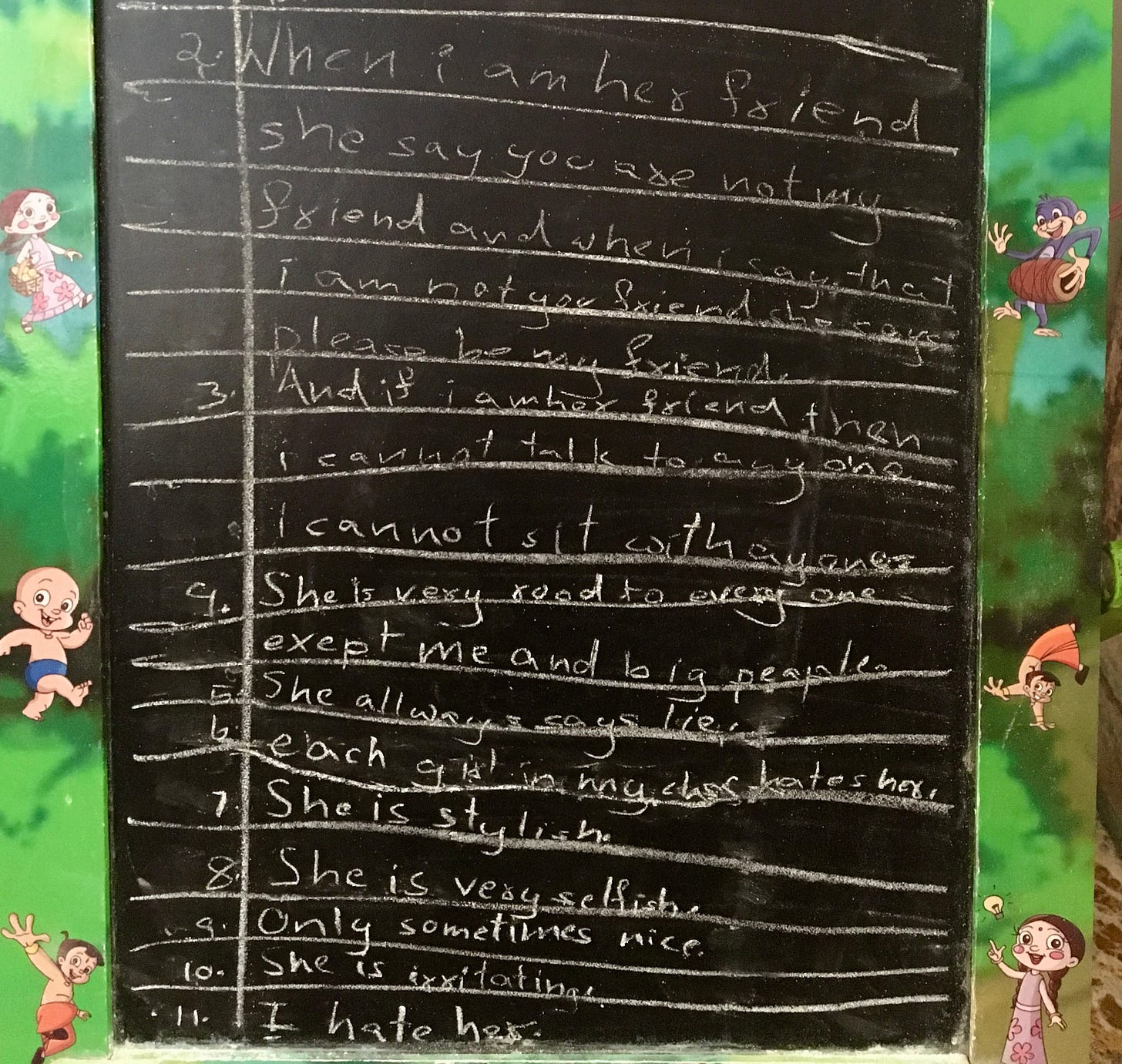

On her blackboard at home, my daughter writes a few lines on her. “Ananya is rude to everyone except big people and me.” She has zero-ed in on details that don’t fit the happy picture of a healthy friendship. She is fearful of what Ananya might say to her when they are alone together.

“I hate her,” she concludes the mini-essay on her blackboard.

I tell her that she must say no to any experience that doesn’t feel good. She can un-choose what happens around her. Her boundaries belong to her.

I read other people’s essays on bullying and consent to get a perpective. This is the age when children must have the permission to be in control. To be able to preserve their innate dignity.

“Sometimes when I do something bad,” she shares, “I think why do I exist at all?”

“I also feel like that,” I say.

“Then I sit on the floor with my back to the wall and hold myself till I calm down,” adds the child. “I also feel sometimes that I do everything wrong.”

“I will tell all my friends in school that we have a swimming pool at home,” she says to me the next morning. She is referring to the small pond we are creating in our front garden to grow water lilies and host koi fish in the future.

“You can call it a splash pool,” I say.

“And there will be fish in it, she asks.

“Yes,” I say.

“But don't get sharks, okay.”

“Okay,” I say.

“Why can’t I catch this light,” I hear her from the next room a little while later. She has caught a shaft of light coming in from a high window and is playing with it. It falls on her palm, but everytime she closes her fist, it escapes from her grip.

“Maybe you can close it in a box or something,” I goad her on.

She finds a solution soon. I walk into her room to see her toy tea-set arranged in a way that each cup has caught a sliver of light in it. “Light tea,” she says, looking up at me.

Natasha, I look forward to your newsletters for the honesty they express. No illusions. Just life as it is. I keep forwarding them to people I hope will read them. These are such painful times, and the unnecessary pain is caused by human beings who can easily choose to be better, but don't. I love your children too.

Poignant moving innocent and real at same time... that's what's redeeming. Thanks