The real difference between my husband and me

“Why would you want to meet people who regard you with suspicion,” I ask him.

My husband Afzal was going to be in Amritsar for one night and I offered to book a room for him online. Besides the fact that I am a good person and like to be helpful to others, this also ensured that I was now safe to spend some time browsing online without him accusing me of wasting my time on the Internet.

My husband is an old-fashioned man who still believes that there is a boundary between the online and offline worlds. I, as you know, like to see myself as trendy, if not a trend-setter.

“Find me something old-world, something classy and charming in Amritsar,” he said.

“I doubt I will find anything like that in Amritsar,” I said to him.

Unlike me, Afzal is not a realist. He can imagine anything anywhere.

I am not only practical, I am also very efficient at following instructions. I found a home-stay with an elegant website, photographs of luminous curtains, enchanting dark wood furniture and a minimalism in aesthetics that made me think that this would be a very expensive place to stay in. I showed the photos to Afzal and no such thoughts occurred to him. He asked me to book a place for him and immediately began to fantasize about a second visit when all of us would stay in these quiet rooms together.

“People like these probably don’t like children on their property,” I said to him. “We will have to speak in whispers.”

The difference between Afzal and me is that he is a dreamer and I am a khadoos, a grouch.

I called the number mentioned on the website and spoke to a very gracious, polite woman who was the owner of the home-stay. I spoke in my most courteous manner to match hers. She had grown children who had moved away and now there was this big house. The home-stay concept ensured they had company every now and then and it helped maintain the estate also. I agreed with everything she said. We discovered common friends and nostalgic connections to Pondicherry. She told me of the room charges. She said he could pay when he arrived; a room would be ready for him.

“Money is not important, people are important,” she said.

“Yes, of course,” I said.

She gave me the number of the caretaker who would open the door if she was not there. Everything was feel-good about our conversation. It had the instant high of many online and phone chats where we seem to connect quickly with strangers who reaffirm our faith.

Finally, as we began to close the conversation, I told her my husband’s name.

After she heard his name, the lady didn’t sound so articulate on the other side of the phone. I wasn’t quite sure what had happened as I hung up.

I called her back half an hour later and asked her the question directly.

“I felt some hesitation on your part before I hung up last time,” I said.

“No, it’s not that,” she said. “I want you to make a full payment in advance by online bank transfer.”

“Is there a problem because you heard a Muslim name?” I asked her.

“We have to be careful, you know,” she said. “My husband and I had some Muslim friends ourselves,” she said. “It’s not that we don’t like Muslims. You know how the world is these days.”

She then told me an elaborate story about a Muslim woman who had come to stay as a guest, borrowed some money from her and later duped her. She worried that she had to maintain records and share information about their guests with the local police and she would have to answer awkward questions about Afzal’s stay. She said her husband wasn’t well enough and she was stressed.

I told her I would call her back. This is when I discovered the real difference between Afzal and me.

I narrated the episode to him and told him that there was no need to stay with people who were going to regard him with suspicion because they equate Muslims with terrorists and con men. He insisted that he would stay with this couple with the posh accent and elegant property in Amritsar.

I immediately wrote them off and Afzal was sure that he had to engage with them. I was offended. He was calm. He wanted me to make the advance payment online.

“It is important for this woman to meet me, Natasha,” he said to me. “What good will it do if we get offended and start fighting with people who we thought are just like us? How will we deal with those who are really dangerous if we don’t dare to face up to those who are our own?”

“Look, I will book you a really fancy room somewhere else,” I said, now feeling rash and willing to do what I would otherwise have argued was a waste of money.

“This woman needs to meet people like me,” he said. “Trust me, I have studied in TD College in Jaunpur. Tilak Dhari Singh Chhatri Inter College was a senior school for upper-caste Hindu boys. I was the only Muslim in my batch. Boys would come looking for me by name just to see what I looked like. The son of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) leader in the city became my best friend. He took me under his wing protectively. Eventually I was the favourite of the teachers.”

“So you think this lady will see your beautiful face and twinkling eyes and feel better about the world?”

“Exactly,” he said. “I’m sure she has a beautiful, antique porcelain tea-set. I want to have tea with this couple. It will be charming.”

The difference between Afzal and me is that while I spend a lot of time worrying about the state of the world, this man always has a good cup of tea on his mind.

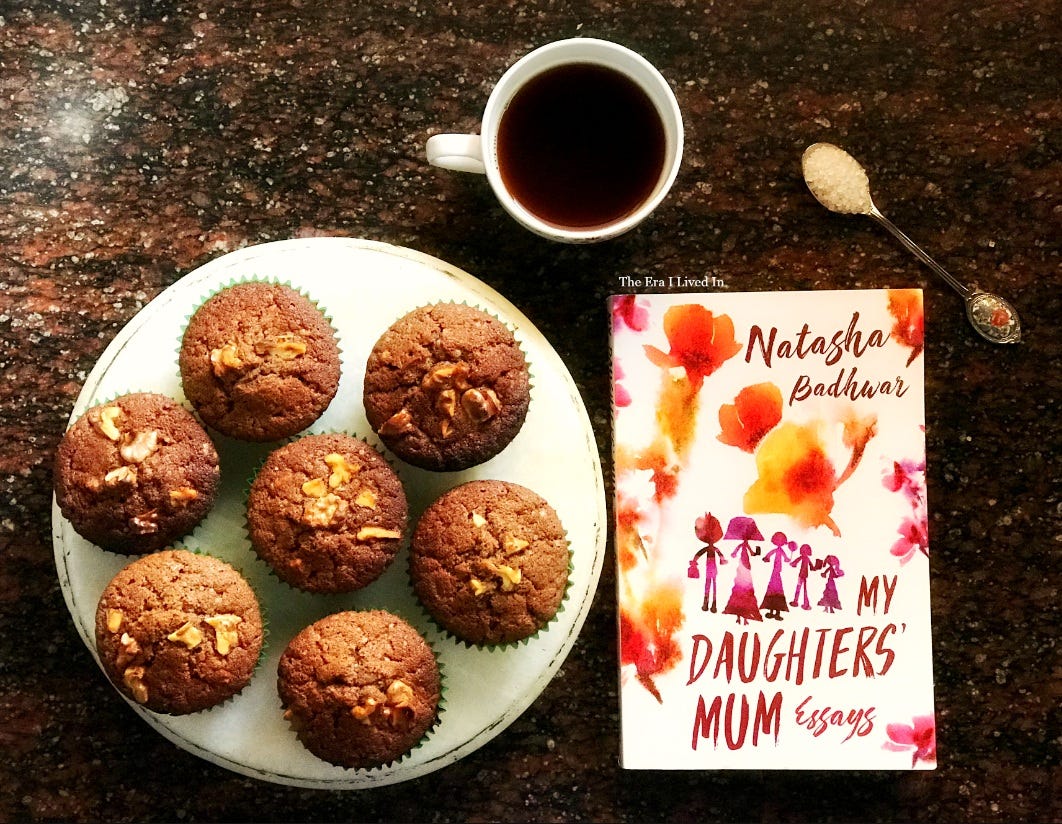

An excerpt from the chapter “You May Say I Am a Dreamer” in the memoir, “My Daughters’ Mum” by Natasha Badhwar, published by Simon & Schuster India.

what a lovely lesson!

thanks for sharing this, Natasha. one has to admire Afzal's steadfast cheeriness in the face of what can be extremely frustrating and disheartening. this was also an enlightening read in that it adds to something I wrote on how Indian Muslims are choosing to go for more "generic" baby names, given our political climate. these names are such that they could blend across cultures, like Sameer or Sahil or Rehaan or, if girls, Zoya or Zara. i hope more families can gather the energy to instead do the hard thing, like Afzal, and be themselves as they are.