Denied permission to visit her father's grave

Sanobar Sabah is a defiant daughter advocating for the right of every woman to pay respects at the grave of those they love and mourn.

Listen to Sanobar’s story in her own powerful, evocative voice:

It was cool and breezy with intermittent rains on 14 July, 2022 – Mumbai’s maddening monsoon showed its divine mercy on my father’s funeral. As I recited the Quran and let my tears flow, I couldn’t help but marvel at the beautiful weather and how serene it felt. Looking out from the ladies’ mosque in Andheri, it appeared as if the Universe had opened its arms wide in anticipation of my father; the heavens had orchestrated a grand welcome for him. I soaked in the lovely hues of the sky and sacred white sheets of clouds.

Soon the women in our family were gestured by the men in the family to bid our goodbye to my father. It was time for the janaaza prayers. As soon as we were done, the men left in a group, asking us to stay back.

I was not ready to be left behind

I live in the UAE and know that Muslim women in the Gulf are allowed to visit graveyards. I had high expectations from Mumbai – one of the most modern cities in the world. Surely we would have ways to manoeuvre through age old customs here.

I requested the muezzin of the Andheri Qabrastan for his permission so I could enter the graveyard and pay respects to my father after the burial. I was told that I was forbidden from visiting my own father’s grave. This, in a place like Mumbai.

The muezzin was polite with my mother and me. He offered us the option to stay at the entrance of the graveyard. That’s as far as women are allowed to go, apparently.

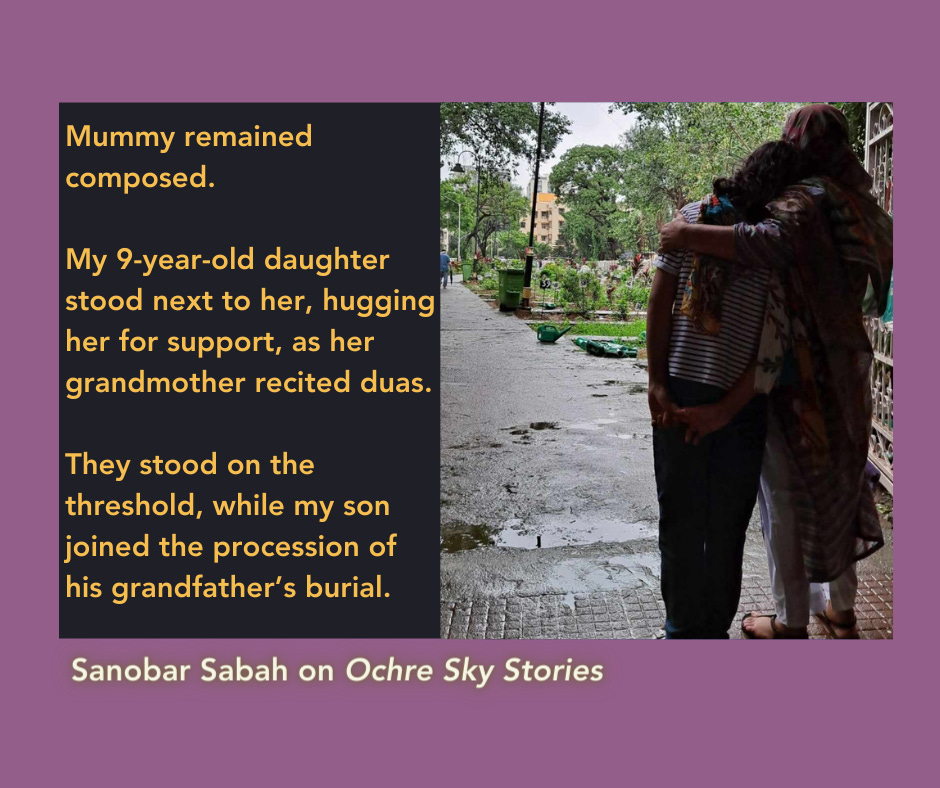

Mummy remained composed. My 9-year-old daughter stood next to her, hugging her for support, as her grandmother recited duas.

I wondered how she would process this later as she stood on the threshold, while her brother joined the procession of their grandfather’s burial.

“Aurtein qabrastan mein nangi nazar aati hain, beta,” said the old woman who works as a cleaner in the Qabrastan. Women who enter a graveyard appear naked to others.

I was incensed at the nonsense but decided not to create a commotion. After bidding our goodbyes, we returned home.

An unforgiving anger

What I didn’t realise was how much that experience would disturb me from within. Like most fathers and daughters, I shared a strong bond with my father. Why was I prevented from visiting his resting place, despite promising to stay respectful and mindful of the graveyard decorum. I stayed awake until the wee hours, crying my heart out with sheer helplessness and unforgiving anger at the hypocrisy and unjustness of the Qabrastan.

I spent hours researching but I failed to find any credible information in Islamic history that states that Islam forbids women from visiting graves. Someone shared with me a video of Omar Suleiman, a revered, young and popular Islamic scholar in the West on how Prophet Muhammad encouraged women to visit graves, just as he encouraged men. I watched the video again and again and saved it to share it with the Qabrastan officials.

A heart-broken, persistent, naive idealist

For the next few days, I was that odd, persistent woman visiting the Qabrastan, pleading to see anyone in authority. The relentless idealist in me saw scope for a dialogue and progress. May be, just maybe, if I shared credible research and experiences from around the world, our women would be allowed to visit the community graveyard after all.

The Andheri Qabrastan officials finally yielded and I was allowed to see the Mufti as well as their Trustee. I entered the meeting filled with optimism - only to be admonished for my ‘ignorance’. My research was greeted with suspicion and mockery.

I resorted to using sarcasm as a defense tool, “Tajjub ki baat hai ki Pakistan aur Saudi Arabia jaisi jagaon mein aurton ko Qabrastan jaaney ki ijaazat hai magar Mumbai jaise barey sheher mein nahin.” It is astonishing that Muslim women in so-called conservative places like Pakistan and Saudi Arabia are allowed to visit graveyards but the Muslim women here, in a big, modern city like Mumbai can’t.

The Shia graveyard, a stone’s throw away from our Andheri Sunni graveyard allowed women to enter their graveyard too, I continued unabashedly, hoping against hope that common sense would triumph over years of ignorance. The tension in the room was palpable. A middle-class Muslim woman demanding her rights in a room with authoritative male figures was not being appreciated at all. Every argument of mine was met with a ridiculous rebuttal and, I was asked to leave. It was made obvious that I was being ignorant and disrespectful. The men exchanged glances and sniggered as I tried my best to convince them.

To say I felt extremely humiliated would be an understatement

Meanwhile, I discovered that my Muslim women friends in Delhi, Bangalore and Hyderabad have been visiting graveyards without any trouble. My indignation and incredulity intensified with each passing day.

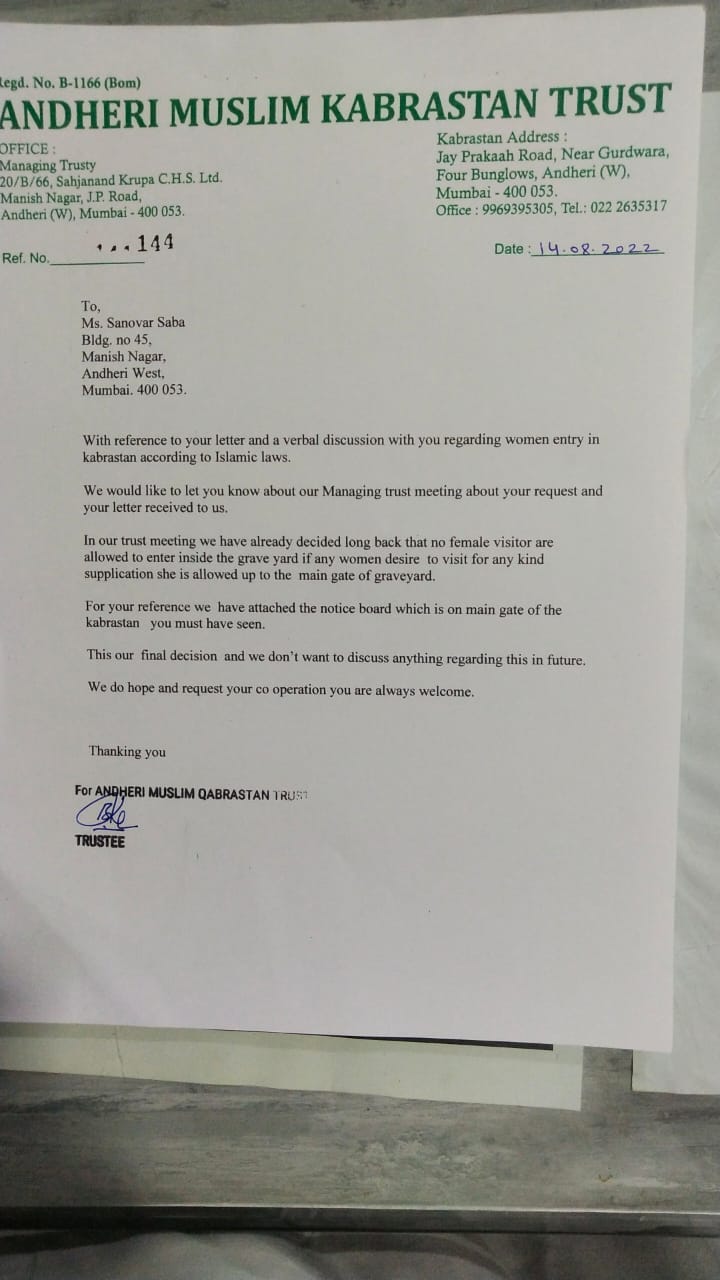

I tapped into my network and called some lawyers and journalist friends. As advised by a Mumbai-based lawyer, I drafted a formal letter addressing the Qabrastan Trustee and delivered the letter to him by hand. Armed with conviction, I informed the officials present in the Qabrastan office that the Qabrastan is bound by the law of land; that the Supreme Court dictates that women are allowed to visit graveyards. As advised, I invoked the Sabrimala temple case and the Haji Ali ruling regarding the entrance of women at places of worship.

The letter must have stirred something as the Trustee’s tone suddenly became friendlier. However, the Mufti was visibly agitated. We clearly did not like each other. The Trustee made one last ditch effort to dissuade me. He attempted to ‘educate’ me by saying that my prayers for my father will be accepted from anywhere. I responded that the same applies to him and that he does not ‘need’ to visit the Qabrastan either.

“Kya haasil hoga qabr par jaa kar? I was asked. What are you going to gain by visiting the graveyard?

“Wahi jo aapko haasil hota hai - tasalli, sukoon,” I answered. I’ll gain what you gain – peace and contentment.

Women friends and relatives tried to comfort me. Many agreed that they find the Qabrastan’s rule bizarre. Not the men in my family though. They asked me to ‘calm down’. There’s deafening silence from many.

I understand that I’m asked to ‘calm down’ because they’re worried about me. I get it. Fear speaks many languages – one of them is silence.

A day before I travelled back to Abu Dhabi, the Trustee informed me that I was being granted permission to visit my father’s grave just once. He made a big deal of how that wasn’t the norm but he was making an exception for me this one time only because he sympathized with me.

I turned down a special offer

To my own surprise, I instinctively turned down this ‘special’ offer. I said that I do not want privileged access to the graveyard. I was not looking for a jugaad solution. No backdoor entries!

I genuinely wanted to change what’s allowed to Muslim women in India. It has to be everyone’s right. Unfortunately I was told that any such intervention would create a huge ruckus for the Qabrastan.

By now, Muslim women I know from India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, America and Canada had shared their stories with me about being able to visit their loved one’s grave without a hassle. I am stunned at the double standards. This exclusion has nothing to do with religion.

The Muslim male clergy is clearly out of sync with both the Islamic teachings and, worldly progress around them. I contemplate a court case against the Qabrastan; I decide against it.

A Muslim journalist friend joked saying, “Ye toh sansani khez headline ban skti hai…Mumbai ki musalman aurtein sirf Qabrastan mein dafnayi jaa skti hain, magar ziyarat nahin kr sktin!” This makes for a sensational headline. Muslim women in Mumbai can visit the graveyard only to be buried. They are not allowed to pay respects while they are alive.)

And that is exactly what I seek to avoid – to make this a clickbait headline. I do not wish to strip the issue of its legitimacy thereby preventing it from being a genuine opportunity for dialogue within the Muslim community.

I do not intend to politicize the issue, especially given the wave of Islamophobia in India.

Stuck in the midst of this quagmire, I’m swamped by conflicting emotions. I want to challenge India’s regressive Muslim male clergy and I also want to protect my own people from the mindless wrath of right wing Hindutva politics.

I join a memoir writing workshop

Channeling my grief and energy into something productive, I turn towards writing - using words as a medicine to heal my wounds. Writing is my last-ditch effort to reach out to like-minded folks from within my community – hoping it would bring about the change my heart so badly desires.

I find myself standing at crossroads now. Rejected by the gatekeepers of my own community, I am worried about a political stunt by the other. Ironically, the opposing agencies have oddly come in unison to silencing us - the women of the community.

So where do we Muslim women go?

Should I speak up or should I calm down, as I have been advised? I’ve made my choice. 14 July, 2023 will mark a year since Dad’s funeral. I haven’t returned to India since then. I would like to.

I would like to visit my father’s grave.

Sanobar Sabah wrote this essay in response to the prompt “Taboo” in the Ochre Sky Memoir Writing Workshop she attended.

Ochre Sky Stories showcases the transformative power of storytelling, featuring the most evocative writing from the Memoir writing workshops conducted by Natasha Badhwar. This is a place to practice authenticity. To reclaim the gift of vulnerability.

Taboo was conceived in the first Ochre Sky Stories workshop. It took birth following the second OSS workshop I attended this year. Thank you for showing me how to give words to my grief, to my fears and then, how to use words to display courage.

Sanobar, your rage is tender and beautiful.